Delaware and Hudson Railroad Bibliography

Books and Articles by S. Robert Powell

All of the items listed in this D&H Bibliography can be read on-line (do a Google search for each by its title) or via Internet Archive.

A. Books:

Twenty-nine volumes, illustrated, on the history of the Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad and the Delaware and Hudson Company by S. Robert Powell. There are 12,016 pages in the 29 volumes. Each volume is a separate book in an electronic format (one or more pdf files) on one archival DVD. To read, insert each disc into a computer and scroll through the text.

I. Gravity Railroad: 1829 Configuration: 271 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-0-5

II. Gravity Railroad: 1845 Configuration: 267 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-1-2

III. Gravity Railroad: 1859 Configuration: 493 pages, illustrated ISBN: 978-0-9903835-2-9

IV. Gravity Railroad: 1868 Configuration: 601 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-3-6

V. Gravity Railroad: 1899 Configuration: 291 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-4-3

VI. Waterpower on the Gravity Railroad: 144 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-5-0

VII. Working Horses and Mules on the Gravity Railroad: 226 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-6-7

VIII. Passenger Service on the Gravity Railroad: 360 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-7-4

IX. Farview Park: 290 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-8-1

X. The Steam Line from Carbondale to Scranton (the Valley Road): 341 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9903835-9-8

XI. The Jefferson Branch of the Erie Railroad (Carbondale to Lanesboro): 354 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9863967-0-0

XII. Reaching Out: D&H Steam Lines beyond the Lackawanna Valley: 687 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9863967-1-7

XIII. Troubled Times—the 1870s: 291 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9863967-2-4

XIV. Carbondale Stations, Freight Houses, and the Carbondale Yard: 241 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9863967-3-1

XV. Locomotives and Roundhouses: 465 pages, illustrated, ISBN: 978-0-9863967-4-8

XVI. Rolling Stock: Freight and Passenger: 475 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-9863967-5-5

XVII. Anthracite Mining in the Lackawanna Valley in the Nineteenth Century: 741 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-9863967-6-2

XVIII. Breakers: 710 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-9863967-7-9

XIX. The Stourbridge Lion: 432 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-9863967-8-6

XX. The Honesdale Branch of the D&H: 386 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-0-9863967-9-3

XXI. The Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902: 289 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-1-5136-2662-8

XXII The People: the D&H, the Community: 518 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-1-5136-2665-9

XXIII The Quality of Life in the Lackawanna Valley in the Nineteenth Century: 672 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-1-5136-2664-2

XXIV The Birth and First Maturity of Industrial America: 634 pages, illustrated, ISBN 978-1-5136-2666-6

XXV Delaware and Hudson Railroad, 2018: Addendum I (December 31, 2018) to S. Robert Powell’s Twenty-four Volume Series on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad. 444 pages

XXVI Delaware and Hudson Railroad, 2019: Addendum II (December 31, 2019) to S. Robert Powell’s Twenty-four Volume Series on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad. 412 pages

XXVII Delaware and Hudson Railroad, 2020: Addendum III (December 31, 2020) to S. Robert Powell’s Twenty-four Volume Series on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad. 400 pages

XXVIII Delaware and Hudson Railroad, 2021: Addendum IV (December 31, 2021) to S. Robert Powell’s Twenty-four Volume Series on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad. 334 pages

XXIX Delaware and Hudson Railroad, 2022: Addendum V (December 29, 2022) to S. Robert Powell’s Twenty-four Volume Series on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad. 247 pages

B. Articles:

All of the articles about the D&H by S. Robert Powell that are listed below have been published in the Bridge Line Historical Society Bulletin, the premier periodical at present on the Delaware and Hudson Railroad and Canal.

1. “The Four D&H Car-Building Contests” (May 2018, p. 7)

2. “The Four Carbondale D&H Roundhouses” (June 2018, pp. 8-10)

3. “More on Owney, the Celebrated Traveling Dog” (July 2018, p. 6)

4. “D&H Challenger #1502 on the Carbondale Turntable” (September 2018, pp. 12-13, 15)

5. “How Did Owney Die?” (October 2018, p. 6)

6. “Photos of the 1925 D&H Car-Building Contest” (October 2018, pp. 12-13)

7. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: Five Configurations (Part 1)” (November 2018, pp. 11-12)

8. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: Five Configurations (Part 2)” (December 2018, pp. 12, 14)

9. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: Five Configurations (Part 3)” (January 2019, pp. 8-10)

10. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: Five Configurations (Part 4)” (February 2019, pp.16-17, 20-21)

11. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: Five Configurations (Part 5)” (March 2019, pp. 12-14, 20)

12. “Industrial Archaeology 101: What Are We Looking At?” (April 2019, pp. 8-10). This is an article about the Honesdale and Clarksville Turnpike and the D&H Gravity Railroad.

13. “The Saratoga Express” (May 2019, pp. 7, 10)

14. “The Boston Express” (June 2019, p. 16)

15. “D&H Baseball: An Introduction” (July 2019, D&H baseball player on cover, article, pp. 16- 17, 19)

16. “Roebling’s System of Anchoring the Cables on the Four D&H Aqueducts” (September 2019, pp. 16-17, 21, 28)

17. “The Birth of the D&H as a Steam Railroad” (October 2019, pp. 16-17, 19)

18. “Compression and Tension in the Four Roebling D&H Aqueducts” (November 2019, pp. 16- 18, 20-21)

19. “Use of Conglomerate Rock in the D&H Canal and Gravity Railroad (Part 1)” (December 2019, pp. 16-18)

20. “Use of Conglomerate Rock in the D&H Canal and Gravity Railroad (Part 2)” (January 2020, pp. 16-18)

21. “The D&H Flat-Land Gravity Railroad” (February 2020, pp. 12-13)

22. “The Legal Battle between the D&H and the Pennsylvania Coal Company,” (March 2020, pp. 16-17)

23. “Regular Passenger Service on the D&H Began in 1860” (April 2020, pp. 16-18)

24. "It Wasn't Only Anthracite Coal that Was Transported on the D&H Canal" (May 2020, pp. 15-16, 30)

25. “The Seven Photographic Series of Ludolph Hensel” (June 2020, pp.16-17, 19)

26. “The Two Trestles on the Jefferson Branch of the Erie Railroad” (July 2020, pp. 12-15, 17, 21)

27. “D&H Gravity Railroad and Mines Shut Down by Horse Epidemic in 1872” (September 2020, pp. 16-18)

28. “The Ararat Cut on the Jefferson Branch of the Erie Railroad” (October 2020, pp. 16-18)

29. “A New Door Has Now Been Opened on the History of the D&H Canal” (November 2020, pp. 14-16)

30. “The D&H, Anthracite Coal, and the Dunmore Cemetery” (December 2020, pp. 12-14, 17, 21)

31. “The D&H Gravity Railroad: 1845 Configuration--Level No. 4, Plane No. 5” (January 2021, pp. 15-17, 22)

32. “The Telegraph and the D&H” (February 2021, pp. 15-17, 35)

33. “Huckleberries and the D&H Mining and Transportation Operations” (March 2021, pp. 6-7, 15)

34. “Passenger Service on the D&H Gravity Railroad, Carbondale to Honesdale (Part I)” April 2021, pp. 15-18)

35. “Passenger Service on the D&H Gravity Railroad, Carbondale to Honesdale (Part II)” (May 2021, pp. 15-17, 19, 29)

36. “Farview Park on the Moosic Mountain on the D&H Gravity Railroad” (June 2021, pp. 1, 15-18, 45)

37. “Lake Lodore Amusement Park on the Honesdale Branch of the D&H” (July 2021, pp. 15- 18, 19)

38. “Delaware and Hudson Bulletin Collection Donated to UAlbany Archives by Carbondale Historical Society” (September 2021, pp. 16, 18)

39. “Inclined Planes on the Delaware & Hudson Gravity Railroad and Canal” (October 2021, pp. 16-19)

40. “Maps of D&H and Pennsylvania Coal Company Operations” (November 2021, pp. 14-15)

41. “The 1824 Delaware and Hudson Canal Company Map” (December 2021, pp. 16-18)

42. “The Gravity-gauge Steam Engine Honesdale” (January 2022, pp. 11-12)

43. The D&H ‘Assembly Line’ from the Anthracite Coal Fields to Tidewater and Beyond (February 2022, pp. 15-16)

44. “D&H Coal Breakers and Collieries” (March 2022, pp. 15-17)

45. “Anthracite Coal Clarifications” (April 2022, pp. 16-18, 20-21)

46. “Coe F. Young and Horace G. Young: Father and Son: D & H Managers” (May 2022, pp. 16-18)

47. “Rollin Manville and C. Rollin Manville, Father and Son, Superintendents of the Pennsylvania Division of the D&H” (June 2022, pp. 16-18)

48. “The McMullen Family: D&H Pennsylvania Division Managers” (July 2022, pp. 16-18)

49. “Thomas Dickson, Empire Builder and Gentleman (Part 1)” (September 2022, pp. 16-19)

50. “Thomas Dickson, Empire Builder and Gentleman (Part 2)” (October 2022, pp. 15-16, 18)

51. “Thomas Orchard: Architect and Master Car Builder for the D&H” (November 2022, pp. 16-17, 23)

52. “White Pine and White Oak Lumber in Roebling’s Four D&H Aqueducts” (December 2022, pp. 16-17, 19)

53. “Waterpower on the D&H Gravity Railroad” (January 2023, pp. 16-17, 20)

54. “The Lease Question, 1873-1874”) (February 2023, pp. 15-18)

55. “Building a Railroad in the Wilderness, 1827-1829” (March 2023, pp. 15-17, 20)

56. “The D&H Bank, Fractional Currency, and Obsolete Bank Notes” (April 2023)

57. "William H. Richmond: Entrepreneur, Coal Baron, Philanthropist" (May 2023)

“Benjamin Wright and John Jervis and the Delaware and Hudson Canal and Gravity Railroad” (published on Internet Archive on February 5, 2022)

“The Switchback at Panther Bluffs on the Honesdale Branch of the Delaware and Hudson Railroad” (published on Internet Archive on May 25, 2022)

* * * * *

Map showing rope ferry across the Delaware River, just above the junction of the Lackawaxen and Delaware Rivers

The Use of Inclined Planes on the D&H Gravity Railroad and Canal

By S. Robert Powell, Ph.D.

The inclined plane is one of the six classical simple machines--lever, pulley, screw, inclined plane, wedge, wheel and axle--developed by man to facilitate the performance of work. Those machines, each of which uses a single applied force to do work against a single load force, are all mechanical devices that change the direction or magnitude of a force. One of those simple machines, the inclined plane, was integrated in the transportation system that was designed for the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company by both John Jervis (Gravity Railroad) and Benjamin Wright (D&H Canal).

An inclined plane is a simple machine that consists of a sloping surface connecting a lower elevation to a higher elevation. Using such a plane makes it easier/takes less force to move an object in an upward direction than it does to lift the object straight up, and this is because the inclined plane increases the distance that the object must be moved.

Raising and Lowering Freight and Passenger Cars on the Gravity Railroad: On the Gravity Railroad, the use of inclined planes has been well documented in the author’s 24-volume series on the D&H, notably in Volumes I-VI. As is well known, loaded and light coal cars, freight cars, and passenger coaches were pulled up or lowered down inclined planes by stationary steam engines. When the Gravity line opened in 1829, most “cuts” of loaded coal cars that were pulled up the planes by stationary steam engines consisted of four cars, each of which contained five tons of coal. Ironically, the inclined planes on the Gravity Railroad, in fulfilling their mission, were used to make work against gravity easier.

On the levels between the planes, as constructed in 1829, horses pulled those same loaded and light coal cars, freight cars, and passenger coaches up very gently sloping inclined planes from the head of one plane to the foot of the next. Across Rixe’s Level/the Summit Level, 1829-1845, a horse could pull no more than two loaded coal cars, in each of which were five tons of coal. When the 1845 configuration of the line was installed, those same levels were all graded so that the loaded and light coal cars, freight cars, and passenger coaches moved by gravity down very gently sloping levels/inclined planes from the head of one plane to the foot of the next.

Raising and Lowering Boats on a Canal: Raising and lowering boats as they move through a canal, as all the world knows, is made possible by the locks in the canal. The “work” performed by the locks in a canal is wholly analogous to the “work” performed by the inclined planes, in the raising and lowering of passenger and freight vehicles on a railroad such as the D&H Gravity Railroad. The locks on a canal, in other words, function like inclined planes. The stretches of the canal between the locks, through which the canal boats are moved by mules or horses are, for all intents and purposes, true levels.

A loaded canal boat, headed for Rondout, for example, is moved into a canal lock and snubbed securely, and the gate at the rear of the canal boat is then closed. The paddle gate in the lock at the head of the canal boat is then opened, causing the water level in the lock to decrease. The canal boat, accordingly, is thus lowered to the level between the lock that the boat is passing through and the next lock in the system. This lowering of a canal boat that takes place as the water in the lock is released through the lower paddle gate is analogous to the lowering of freight and passenger vehicles on the Gravity Railroad as they move down a plane.

Similarly, an empty canal boat, or any boat going up the canal, is moved into a lock and securely snubbed. The canal gate at the rear of the boat is then closed and the paddle gate at the head of the boat is opened, which raises the water level and the canal boat in the lock to the height of the level between the lock through which it is then passing and the next lock on the canal. This raising of a canal boat that takes place as the water in the level at the head of the canal boat enters the lock through the paddle gate at the head of the canal boat is analogous to the raising of freight and passenger vehicles on the Gravity Railroad as they move up a plane.

Shown here is a detail of the map of junction of the Lackawaxen River and the Delaware River (surveyed in 1854, map drawn in 1856 by E. W. Weston, Honesdale, and revised in 1865) on which are shown D&H Pennsylvania Lock No. 1, the Lackawaxen River, the location of the piers on both shores of the D&H rope ferry across the Delaware River, and the location of the Ferryman’s House on the New York shore.

Moving Canal Boats and Horses/Mules across the Delaware River: The several histories of the Delaware and Hudson Canal now in existence note that, in the period 1828 to the opening of the Delaware Aqueduct in 1849, the boats on the D&H Canal were moved across the Delaware River at Lackawaxen by means of a rope ferry. How does a rope ferry function? An excellent description of how a rope ferry was operated in the nineteenth century is presented in James Otis’ Benjamin of Ohio, A Story of the Settlement of Marietta. (James Otis Kaler, 1848 ?-1912, was an American journalist and author of children’s literature, who wrote under the penname James Otis).

On pages 27-28 in the December 9, 2019 edition of Benjamin of Ohio, we read the following about a rope ferry on the Lehigh River:

“And so we journeyed on without adventure until we came to the Lehigh River, and there I saw what I dare say no fellow in Massachusetts has laid eyes upon. It was called a rope ferry, by means of which we were to cross the river [emphasis added].

“Ben Cushing claims that there is nothing wonderful about this ferry, for it consists simply of a rope stretched from one bank of the river to the other; to this, attached by a noose, or, in other words, a hawser [Hawser is a nautical term for a thick cable or rope used in mooring or towing a ship. A hawser passes through a hawsehole, also known as a cat hole, located on the hawse], which will readily slip, the ferryboat is made fast in such a manner that the stern is lower downstream than the bow, and the current catching this, forces the boat along.

“Perhaps I haven't made this very plain to you, but it is operated on the principle of force applied to what might be called an inclined plane [emphasis added]; therefore, since the craft cannot be shoved downstream by the current, it must be urged toward the opposite shore.”

What is known about the rope ferry on the D&H Canal and how it operated? In Manville B. Wakefield’s Coal Boats to Tidewater, pp. 81-82, we read: “As the canal was originally built, the loaded boats drooped down through three locks, Nos. 3, 2 and 1 respectively, to the rope ferry crossing. On the New York side light boats moved out through a guard lock to the stilled pool of water above the dam [built in 1827 by the D&H across the Delaware River just below the confluence of the Lackawaxen and Delaware Rivers to create an area of still water for the floating across the Delaware River of canal boats]. [Wakefield then quotes John Willard Johnston, Reminiscences and Descriptive Account of the Delaware Valley and Its Connections Aiming to Extend from Pond Eddy to Narrowsburg, 1900] ‘A towpath was formed along the river edge [on the New York shore of the Delaware River] a distance of ½ mile. . . to a point where a ferry was erected; by means of a pier stationed at the opposite side of the river composed of four foot square pine timbers locked together at the corners and the interior thoroughly filled with stones. The piers were twelve foot square at the base, about fifteen feet high and contracted to about seven foot square at the top. These piers supported the ends of a ferry rope two inches in diameter stretched across the river from pier to pier. By means of this rope a ferry scow [emphasis added] was guided across the river as occasion demanded.’(p. 37) /

“When the water was at low mark the boatmen [in exiting from Lock No. 1] would urge his horses to an extra burst of speed so as to establish sufficient headway to cause the boat to shoot across the river. This avoided the tedious process of being pulled across by rope. / ‘Many times the loaded boat crossing from the Pennsylvania side would pass over the river and enter the canal in New York before the horse and driver crossing by ferry would overtake it. When, however, the river was swollen by rains, the boats, horses, and all must be crossed by the ferry… Even this was possible only at certain levels of water above which boats could not cross at all and the business of the canal suspended for a time’ (Johnston, pp. 38-42) (end of Wakefield citation).

That material from Wakefield and Johnston is seconded by statements in Volume III of the eight volumes of testimony in the court case between the Pennsylvania Coal Company and the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company. Therein, on pages 1809-1904, the testimony by Peter P. Yaple is reported. Yaple was a boatman on the D&H Canal, who was 45 years old when he testified. He began working on the D&H Canal in 1833 as the captain of a boat. At the time of his testimony, he resided in the town of Rochester, Ulster County, NY. In that testimony, on p. 1834, we read the following:

Question by attorney: “In what manner were boats passed across the Delaware River before the [Delaware] aqueduct was built?” Yaple: “If the river was low, we would give headway to the boat with our horses, and shoot across it, as we call it; and take the horse in a scow and draw it over by a line or cable crossing the river; if the river was high we would run our boat to the scow, and take a line out on the scow and haul the boat over by hand.” Attorney: “Do I understand you, in your preceding answers, to say that this process of crossing was prevented during time of severe freshets until the water should subside sufficiently?” Yaple: “Yes.”

On this same question, we read, on page 443 in Volume I of the account of the PCC/D&H court case, the following statement by Russel F. Lord, who was the Superintendent of the D&H Canal: “…on the old canal [before the Lackawaxen and Delaware aqueducts were opened in 1849] the boats crossed the Delaware River in a pool created by the Delaware dam, using a rope ferry to transfer the horse from one side to the other; by the erection of the aqueduct, the boats now pass direct through it [Delaware aqueduct] over the river, and the horse on a towing-path on the side of the aqueduct.”

Summary statements, based on the data presented above, on how D&H Canal Company boats and the horses that pulled those boats along the D&H Canal crossed the Delaware River at the rope ferry at the junction of the Lackawaxen and Delaware Rivers in the period 1829-1849:

Crossing the Delaware River from the Pennsylvania shore to the New York shore of the Delaware River: If the Delaware River was low, a D&H canal boat captain, in departing from Lock No.1, would give headway to his boat and shoot across the Delaware River. The horse or horses assigned to that boat would be transported across the Delaware River on a scow attached to the rope ferry. If the river was high, the canal boat would be moved across the Delaware River by means of the rope ferry; the horse associated with that boat would be taken across the Delaware by the scow on the rope ferry.

Crossing the Delaware River from the New York shore of the Delaware River to the Pennsylvania shore of the Delaware River: Canal boats, loaded and light, would be taken across the river by means of the rope ferry. The horses associated with those boats would be taken across the Delaware River on the scow that was part of the rope ferry system.

Rope Ferries, Physics, and Geometry: How does a rope ferry function? The rope ferry across the Delaware River, which used the power of the river to tack across the current, was what is known as a “reaction ferry”, which is a cable ferry that uses the reaction of the current of a river against a fixed tether to propel the vessel across the water. Such ferries operate faster and more effectively in rivers with strong currents, such as the Delaware River. Reaction ferries are numerous at the present time in Germany and Poland.

Some reaction ferries, like the D&H rope ferry across the Delaware River, operated using an overhead cable suspended from towers anchored on either bank of the river. Other reaction ferries use a floating cable attached to a single anchorage that may be on one bank or mid-channel.

At the rope ferry pier on the Pennsylvania shore the Delaware River, two ropes (hawsers), both in the form of a noose, were hung on the rope across the Delaware River. These hawsers on the rope across the Delaware River were movable (they are sometimes called “travelers” on rope ferries) and could easily slip/move. The two hawsers were securely attached to the ferry scow (or to a canal boat), one at the bow and one at the stern. The two hawsers were not of equal length. The one at the bow was directly below the rope across the river (the shortest distance between the rope across the Delaware and the canal boat); the one at the stern was longer, perhaps by a third, than the hawser at the bow.

With the scow thus positioned at the pier on the Pennsylvania shore of the Delaware River, the down-river current of the river would push the stern down the river as far as the hawser at the stern would allow. This down-river force on the stern of the boat would cause the hawser at the bow of the boat to slide along the rope across the Delaware, in the direction of the New York shore. The forward motion of the boat would thus cause the stern of the boat to return to a position more or less under the rope across the Delaware. The river would again push the stern downstream, which would again cause the hawser at the bow of the boat to slide along the rope across the Delaware and guide the boat as it moved in the direction of the New York shore. A rhythm would quickly be established, as the canal boat, using the power/the current of the river, in a series of pulsing movements, tacked across the current and moved across the Delaware River.

The distance that the stern of a boat attached to a rope ferry is pushed downstream by the river (from its initial position directly under the rope across the river to the point where the hawser at the stern of the boat is fully extended) is completely analogous to the distance up or down which loaded and light coal cars or passenger cars were moved on a plane or level by a stationary steam engine on the Gravity Railroad. The current of the river (on the canal) and the stationary engines (on the railroad) are the sources of the power (work performed) that caused forward movement.

The distance between the position of a boat at the point of maximum extension of the hawser at the stern of the boat to the position of the boat at the point of minimum extension of the hawser at the stern of the boat (under the rope across the river) is wholly analogous to the length of a level on the Gravity Railroad. In geometrical terms, the shape of the movement of a canal boat across the Delaware River, by means of the D&H rope ferry, is, therefore, essentially triangular, as is the shape of an inclined plane or level on the Gravity Railroad.

Structurally, then, the D&H rope ferry can be seen as a series of nautical inclined planes by means of which canal boats (which carried from 30 to 50 tons of coal in the period from 1829, when the D&H Railroad and Canal became operational, to 1849, when the Roebling Delaware Aqueduct was put in service and the Rope Ferry across the Delaware River was no longer needed) and the rope ferry scow on the D&H Canal were moved across the Delaware River from the Pennsylvania shore of the Delaware River to the New York shore, and from the New York shore of the Delaware River to the Pennsylvania shore.

If John Jervis and Benjamin Wright, both of whom had engineering credentials of the highest order and who, therefore, understood the importance of using the classical simple machines that were developed by man to facilitate the performance of work, had not integrated one of those machines, the inclined plane, in the D&H Gravity Railroad and the D&H Canal, respectively, would the D&H have been able to accomplish, efficiently and in a cost-effective manner, the “work” that it did in the nineteenth century? Possibly, but it seems more than likely that they could not have done so. We’ll never know. One thing that we know for certain is that the D&H accomplished, efficiently and in a cost-effective manner, an astonishing quantity of “work” in the course of the nineteenth century. They did so by integrating in that transportation system that John Jervis and Benjamin Wright designed and which the D&H constructed from the Lackawanna Valley to Honesdale and from Honesdale to the Hudson River, a simple machine, the inclined plane.

* * * * ** *

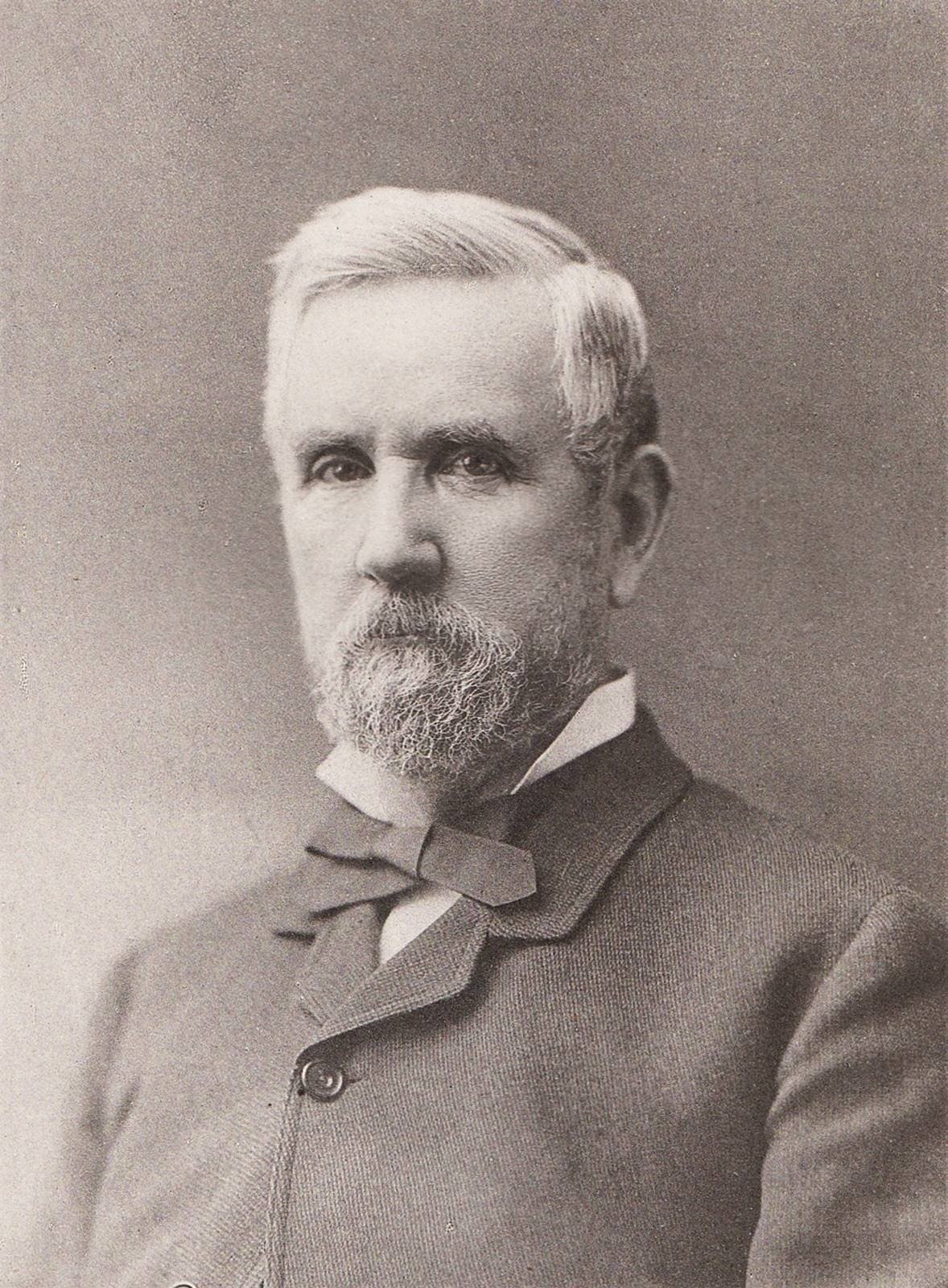

Thomas Dickson